48 Hours as a DC Insider: Racing to Give AI the Energy It Needs

If someone tells you, “May you live in interesting times,” take heed — it’s both a blessing and a curse.

2024 has proven to be very, very interesting indeed, not least because half the world — that is, billions of people — is heading to the polls. As I wrote in previous articles, I had the chance to see the effects of this international election season from Latin America to rural Scotland. Though the US isn’t physically plastered with candidates’ faces the way, say, the streets of CDMX were, there’s a palpable sense of nervous energy about our upcoming presidential elections. Curiously, it seems there is less vicious dialogue than in previous years; perhaps we’re all equally worn out by the convergence of wars, extreme weather events, and overstimulation from social media.

November — and the temporary certainty of knowing who leads the nation — can’t come soon enough.

Unified by Innovation

But hark! Amidst the darkness, embers of a national consensus are stirring: in a manner not unlike that of the Space Race, Americans are increasingly alert and unifying around the advancement of our nation’s scientific and technological capabilities. This isn’t just for innovation’s sake, but as a means to re-shore manufacturing and remain competitive in a globalized world.

Technology has profoundly changed geopolitics and we want to win. We want to lead. The question is how?

With those questions in mind, I headed to D.C. to engage in dialogue about some of the most pressing issues of 2024:

- AI,

- its security risks,

- and the energy needed to power it.

As part of the Schmidt Program on Artificial Intelligence, Emerging Technologies, and National Power, I was part of a group of students trying overcome the partisan noise and provide thorough ethical and technical guidance to decision-makers. The main event we attended was the Special Competitive Studies Project’s AI+Energy Summit. SCSP is a relatively new think tank, emerging from former Google CEO Eric Schmidt’s involvement in the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence. Though NSCAI’s mandate ended in 2017, SCSP was created to continue the conversation.

On the six-hour train down the Eastern seaboard, I was a bit jittery. I’d just spent three years trying to understand how the Bay Area whispers — cracking D.C. felt like starting the whole process over.

From what I remembered about D.C., the last major tech debate had been about net neutrality, and though it’s no longer in the headlines, the rules seem stuck in a pendulum, giving everyone legislative whiplash as they change with each administration. Would the Sisyphean struggle hold true for AI policy?

Either way, I find this coming wave of technological change particularly interesting because:

- It spans various scales, from microchips to nuclear power plants, necessitating a multi-decade transformation that reimagines both critical infrastructure and legal standards.

- Technologists play an outsized role in crafting effective government strategies. Silicon Valley — often justifiably — loves to point out how slow and technically illiterate policymakers can be. These complaints have mobilized the current generation of VCs and founders to become really good at writing (it’s not just because they have access to ChatGPT). Picking up the mighty pen that is Twitter, they’ve advocated for philosophies like American Dynamism, nailed what’s definitely more than Luther’s 95 Theses to the doors of Congress with detailed suggestions for bill reform, and, of course, followed in the Founding Fathers footsteps to publish the Digital-ist Papers.

Before going deeper into the implications of these nuances for AI policy, let’s dig deeper into AI’s current capabilities.

The State of AI

My Schmidt coursework with members of the Digital Ethics Centre and the Socially Assistive Robotics Lab has been useful in reminding me that success in AI builds on decades of research, not 30 seconds of brilliance. Yes, the media makes it seem like advancements are constantly coming in hot, but it’s easy to overestimate the capabilities of AI. There are two reasons for this:

- AI is a moving target across so many industries: progress and increased applicability in one don’t guarantee reliability in another.

- Furthermore, we tend to judge AI success against science fiction, not actual science, so the ease of text, code, or image generation with the press of a button blinds us.

As a result of this uneven progress and unrealistic expectations, we forget that AI can hallucinate. We disregard the fact that AI can’t reason independently, though this will be the focus of the next chapter of progress. Eventually, perhaps we’ll reach artificial general intelligence (AGI), or as Eric Schmidt defines it, “intelligence greater than that of all humanity.”

In a perfect world, we’d be able to develop uncertainty quantifications to more clearly understand what we can trust. This would be especially applicable in healthcare and military, where the consequences of errors are severe. However, the computational burdens of training and retraining models to determine the output possibilities, as well the dynamic nature of environments rendering non-real time data obsolete make this near impossible. Ultimately, this problem shows that some problems are mismatched with the skills of computer scientists and we need mathematicians to keep picking at them.

A Looming Crisis: The Need for More Energy

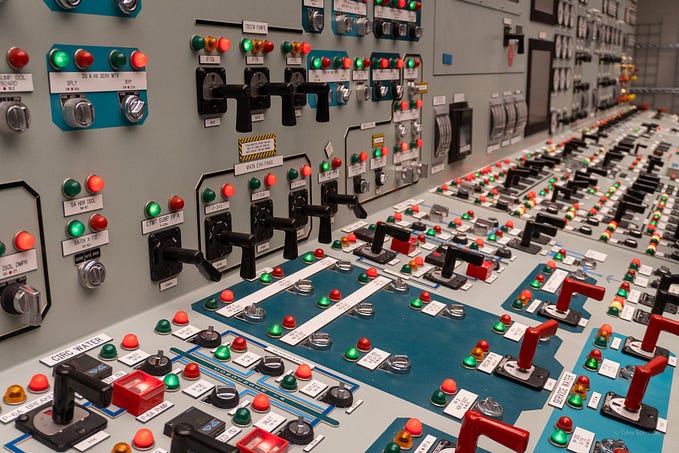

Remember how I said that the AI debate spans multiple scales? Well one step before the above mentioned AI design mechanisms are the data centers containing racks of servers with GPUs necessary to train the models. There’s a few different types of these centers around the world:

- Enterprise data centers — best suited for companies that have unique network needs; they’re usually on site at company HQs/locations.

- Colocation — multi-tenant; have to develop comprehensive customer service offerings to suit the needs of running multiple companies severs at the same time.

- Modular — often found at construction sites or in disaster areas.

- Edge — demand for instantaneous connectivity necessitates computing closer to the actual data.

- Hyperscale — the really big guys; only 700 out of 7M total data centers around the world.

As you might expect, these data centers need a lot of power to run and cool the GPUs. And now, with a single ChatGPT query taking 10x as much as a Google search, 8% of the world’s energy is already being used for AI.

Our aging energy grids are ill equipped to distribute this amount of energy, with most of our transformers being nearly 40 years old and thus vulnerable to causing outages. Hold that thought though because our grids might not even have enough power to distribute for all the residential, industrial, commercial, and data center customers. There’s two outcomes of this crisis: either AI development comes to a grinding halt when the power it’s been allocated isn’t enough OR other infrastructure loses power because AI is taking up so much. Both are issues of national security.

(As an aside — while the history of humanity has been about preservation of information, perhaps it’s time to start thinking about more careful management and even deletion of dark data AKA data that is stored, but not actively used. After all, data creation is expected to reach 147 ZB (yes, zettabytes) by early 2025, over double what it was in 2020. Do we really need it all? Have we become addicted to tracking everything?)

So how do we get more power? In the past few weeks, three tech giants have announced large-scale green energy initiatives — in particular nuclear — to power their data centers:

- Microsoft will support the reopening of Three Mile Island through PPAs (purchase power agreements) with Constellation Energy.

- Amazon bought a Pennsylvania data center powered by a nearby nuclear reactor from Talen Energy.

- Google signed PPAs with Kairos to build a fleet of advanced nuclear plants.

These announcements reflect the growing gap between fossil fuel and green energy investment. In 2016, the two were tied. Now, there is a $700M gap showing that the clean energy transition will be private-led, government enabled. (An appendix below dives deeper into renewables versus green energy.)

The Governance Issue

Now that we have outlined the current capabilities of AI and explained the need for parallel progress in the energy sector, we can turn our attention back to the legislative environment. My primary observation of D.C. is that it’s at a governance crossroads.

- It’s still grappling with accusations of being a “swamp.” Indeed, it’s messy: the government is losing upwards of $233B annually to fraud, $175B in overpayments just last year, and as much as $500B going towards expired “zombie” programs this year. Did I mention the Department of Defense has NEVER passed an audit? Admittedly, Elon Musk’s idea for an Efficiency Commission does a good job calling for accountability.

- There’s a lot of people doing (mostly) necessary busy work. Improvements in communications tech have enabled more and more people to keep up with and reach out to their representatives, placing a greater demand on congressional staffers to supply constituent services rather than get legislative work done. That being said, congressional offices mostly craft policy appealing to voter demands. I’m still trying to understand these dynamics, but it appears that the policy that really affects things — agency rule making — is shaped by thousands of (mostly) well-meaning, deep subject-matter experts. I know most people have a distaste for technocrats, but bear with me . . . we need more, not less, of their technical fluency. Alas, STEM graduates are lured away by more lucrative positions in the private sector.

- This summer’s overturning of the Chevron Deference means rule-making is about to get even slower. By establishing that judges no longer need to defer to federal agencies in interpreting ambiguous parts of statutes, the Supreme Court weakened the powers of agencies. In other words, agencies no longer have the final say on how to interpret gaps in a law that Congress passes, so their actions are up to judicial scrutiny, delaying implementation. This is a rather partisan issue as it shifts power to the judicial branch.

- The government is in a reactive posture, as this is the first revolution in tech not invented by the government. Therefore, companies creating frontier models are not reporting as they used to. All decisions with the private sector are consensus-based as entities like the National Security Council simply do not have command authority. The latest consensus has come in the form of voluntary transparency commitments from Amazon, Anthropic (maker of Claude), Google, Inflection (strengths in enterprise AI and more empathetic, human like “companion assistants”), Meta, Microsoft, and OpenAI. Notedly, even when these tech giants agree to dialogue with government, they seek oversight but don’t want it to turn into regulation. After all, CEOs live in the moment (or the quarter), always keeping an eye on the market. National security isn’t exactly priced in; it’s a longer term game, especially against full spectrum competitors able to treat even our economy as an attack surface. That means the 18 Intelligence Community offices that were designed to win the Cold War are inadequate, though I will give a shout-out to Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) and In-Q-Tel who invest in research programs and startups to tackle some of the IC’s most difficult challenges. Their success stories include Palantir and Anduril.) Therefore, the Departments of Commerce and Energy play crucial roles in this new strategic competition.

Digging into the Key Players

Broadly speaking, the Department of Commerce creates conditions that promote economic growth and opportunity for all communities. On the train back from DC, I dug into a few org charts to understand how all the four letter government sub-agencies fit together. The most relevant ones ended up being:

- the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), within which the U.S. AI Safety Institute is housed,

- the Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO),

- the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) responsible for developing AI system assurance through audits, assessments, certifications, as well as reviewing data center supply chains,

- and the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) setting export controls.

I was curious about the extent to which the actions of public servants within these organizations should remain secretive, but the only thing I was able to find out during our visit to the Department itself was that details of test data are kept hidden to maintain integrity. Maybe the others things being kept secret are a secret . . .

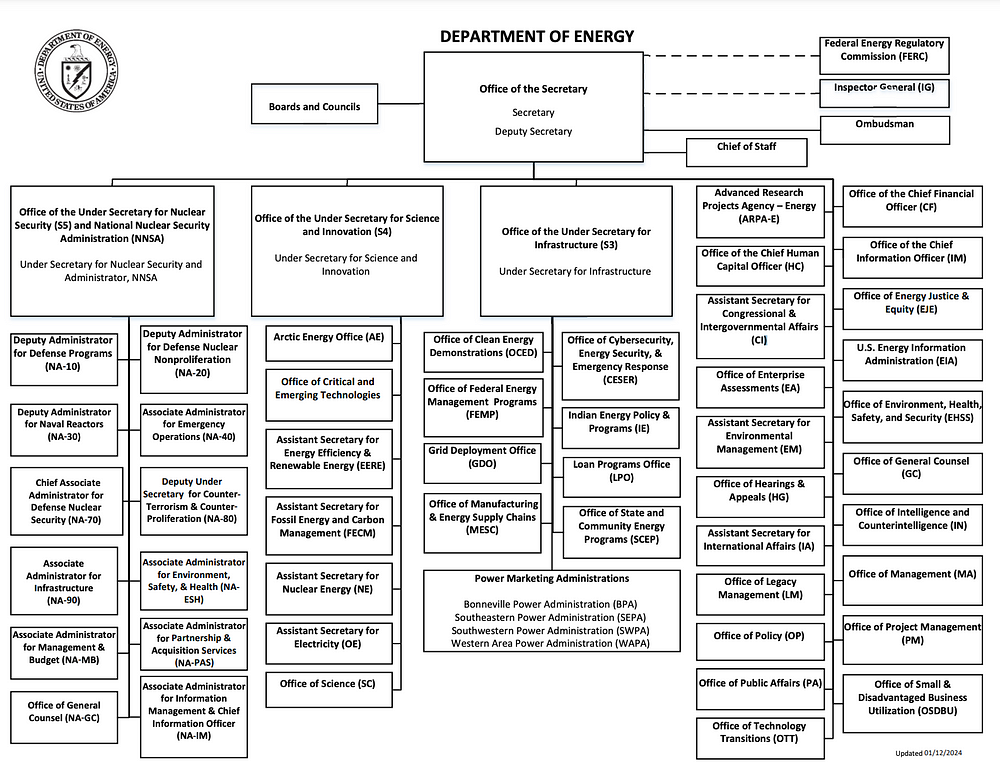

Next up is the Department of Energy — it strives to ensure the security and prosperity of the United States by addressing its energy, environmental, and nuclear challenges.

I personally find Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy (ARPA-E) or the DoE’s DARPA the most interesting government organization. By funding the R&D of advanced energy tech, it acts as an incredibly technically-literate venture capitalist who’s not risk averse; after all, their goal is American advancement and progress, not profit. And check out these successes!

If that wasn’t cool enough, the DoE is also home to 17 national laboratories, including the Lawrence Livermore Lab known for its groundbreaking fusion achievements.

Legislative Headwinds

While it’s complicated enough to navigate the web of D.C. agencies and commissions, here’s a list of a few policies whose implementation (or lack thereof) and possible changes to after the election are worth tracking. A more comprehensive list is available in the AGORA database of the Emerging Technology Observatory, a project of the Center for Security and Emerging Technology at Georgetown University.

First of all is the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights which was designed to “help guide the design, use, and deployment of automated systems to protect the rights of the American public in the age of artificial intelligence.” As such, it promotes five principles:

Searching for brutally honest reactions to the Bill, I came across one assessment that “it is [only] an aspirational ethical framework [ . . . ] by White House policymakers struggling to reconcile existing needs and technical demands with the psychological and perception narratives around the hot-button topic.” It went on to explain that over time legitimate legal precedents will promote codified policies and enforceable standards.

Then, there is the Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence (EO 14110, November 2023). Immediate blowback accused it of executive overreach by invoking the Defense Production Act (typically used in emergency situations relating to national security) to impose reporting requirements on developers of compute heavy AI models. Other specifications of the executive order regard watermarking AI-generated products and instructing The Office of Management and Budget to provide guidelines to federal agencies procuring AI products.

At the state level, California has been one of the most active in addressing AI policy. The state is currently considering SB 1047, the Safe and Secure Innovation for Frontier Artificial Intelligence Models Act, which, like EO 14110, would hold developers increasingly responsible for the impacts of their products. Opponents of the policy argue that requiring developers to submit a statement of compliance with the Attorney General’s office is premature and irresponsible, as they cannot predict all the potential uses of their products by customers.

When it comes to energy and critical infrastructure, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal (2021) has gotten the most attention. It granted $5 billion towards (1) the Grid Innovation Program (BIL Provision 40103(b)) to improve transmission, storage, and distribution infrastructure, as well as (2) expand Smart Grid Grants (BIL Provision 40107) for grid enhancing technologies (GETs). GETs are critical in capturing untapped value in existing infrastructure. Some examples include dynamic line rating to alter safe transfer capacity based on weather conditions and topology optimization, which distributes power more evenly.

Another grid related policy is Section 401 of the Energy Permitting Reform Act (2024). In the interest of national security, it grants the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission the authority to green-light geographically extensive interregional transmission projects to proceed construction even if states block it. Other aspects of the act police transmission authorities in not pursuing projects that push costs to consumers. Transmission line permitting is easily the biggest bottleneck in building out our energy grid, so we need more policy action in this space, perhaps even coordinating cross-border projects with Canada.

The Inflation Reduction Act (2022) is a more controversial investment in domestic energy production and manufacturing, due to its rather deceiving name. Packing in climate investment, healthcare, and corporate tax reform, Biden himself admitted that the bill doesn’t reduce inflation but offers alternatives that generate economic growth. The act drew ire from Republicans as a reckless spending spree — they explain that focus on wind and solar infrastructure degrades US energy security, as it is primarily built abroad. The U.S. International Development Finance Corporation is currently giving out grants to friend-shoring or diversify these supply chains.

Last, but not least is the CHIPS and Science Act (2022). In light of the semiconductor industry’s high concentration in Taiwan, it addresses the necessity of re-shoring the supply chain by pledging $52.7 billion for American semiconductor research. However, the government subsidies are yet to be distributed to key actors and 40% of major manufacturing projects announced in the first year of the IRA and CHIPS Act are facing delays. Last week’s Building Chips in America Act removed the need for National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) reviews, citing (as expected) national security much to the dismay of worker safety advocates.

Implications & Boosting National Attitude

Great! We have a lot of ongoing policy debates raising awareness about AI and energy. Now what?

Going back to what I learned at the Department of Commerce, I was surprised to hear Secretary Raimondo express worry about a persisting national anti-AI narrative. Sure, everyone agrees we can’t fall behind other countries in exploring its capabilities (again — 21st century space race mindset), but people are divided about the extent to which AI is a good thing.

She was right — while my friends and I were excitedly using LLMs to proofread emails and explain class concepts, as well as had access to National Artificial Intelligence Research Institutes, the average American worried about deep fakes, job security, and NIMBYism. In fact, some people have called it a luxury belief to think most Americans would be fine having a nuclear reactor their neighborhood. Raimondo emphasized that if only people further understood the benefits of AI, Congress would be pressured to unlock/fund more R&D to make us even better positioned.

If, however, the anti-AI narrative persists, policies can get even more stringent, limiting the research universities can do and the tools Silicon Valley can put out. This could unintentionally widen the digital divide between the aware, tech-savvy communities and the offline ones, but also between US and other countries more open to AI advancements.

Going back to job security — I’m personally not convinced by narrative of blue collar jobs easily transforming to fit fourth industrial revolution needs, but I agree that we do need more and more electricians to build data centers. Just recently, on September 25th, the NSTC Workforce Center of Excellence received a $250M investment to help train that workforce. We’re seeing similar investments into cybersecurity experts. As a result, the nation is gradually moving towards a larger (hopefully more cautious) and well-educated workforce.

Conclusions

While it was jolting to learn it was Lenin who said, “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” there’s some truth to it.

The past few weeks have brought increased attention to new types of national security: some of these security concerns have simply been evolutionary (addressing aging infrastructure and how government buys technology), but other parts have been absolutely revolutionary (meeting the energy demand by AI and the trustworthiness of its outputs).

Government and private actors have a challenging path ahead of them in developing thoughtful, but flexible regulatory frameworks for the coming years. While there’s a lot of people working on a lot of fronts to get this done, I believe the most urgent — and simultaneously most tricky — legislative issues concern AI liability and transmission line permitting.

I humbly admit I am way too early in my “DC deciphering” to offer any valuable feedback for the governance structures necessary for this wave of new legislature, but I think this call to action is on the right path:

“If we really want to unleash a true techno-industrial state, it’s going to take more than billion-dollar bills. We need deep reforms to address the bottlenecks in our government systems, fix resource mismanagement, and break the institutional inertia holding us back. Without that, we’ll be stuck, no matter how much we spend.”

Appendix — Why Nuclear?

Thinking about US national security, it is critical to diversify energy sources through a combination of continuous and intermittent sources. Though it depends on location, solar is almost always the most quick-scaling energy generation source, bolstered by decreasing manufacturing and installation costs, as well as net metering/sell back opportunities.

The main drawback is that solar panels are usually approx. 20% efficient, based on available sunlight and quality of the photovoltaic cells. Geothermal energy, on the other hand, is more reliable since it can generate power continuously, but it makes up less than 1% of the U.S. energy supply.

Therefore, nuclear appears to be the main way forward. There are two types of it: fission and fusion.

When we say “nuclear,” we usually mean the former (note that the graph is flipped). Nuclear fission reactors split the most unstable and heavy elements with neutron bombardment, causing the emission of kinetic energy. They’re not renewable, but green, as they relies on a finite fuel (uranium). Overall, nuclear fission provides almost 20% of total US electricity generation.

Fusion is the opposite of fission as it relies on fusing two nuclei into a new heavier element, much like happens on the Sun. It’s renewable, but not commercialized yet; Livermore Labs only achieved fusion ignition in 2022, sparking (pun intended) government backing of pilot fusion plants. China, Germany, and the UK are in the same spots or slightly ahead with plant opening goals in the late 2030s. Sam Altman has similarly invested in fusion plant startups. Unfortunately, as with many such projects, there is a workforce shortage (pease get your PhDs y’all), but international exchange of information makes for a “strange story of both competition and collaboration.” We shouldn’t give up on fusion because it produces much more energy than fission in such a way that could one day we used not only to very quickly power data centers, but even zoom through outer space.

In order for boost nuclear reactor deployment across America, the government should promote favorable construction conditions such as through the Advance Act (July 2024). This act authorizes the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to reduce licensing application fees, streamline licensing processes for nuclear facilities at brownfield sites, and assess potential vulnerabilities in the domestic nuclear fuel supply chain.